A Sea like none other

December 13th, 2014 – Leenan Head’s logbook:

«We left Cape Verde ten days ago, and the trade winds have since been pushing us towards the Grenadines. The first Transat of the year is always a special moment. A little over a week from now, our sailing boat will reach the white beaches of the Caribbean. In the meantime, we are surrounded by nothing but open water. Around us and stretching all the way to the slightly curved horizon, is the deep blue. Slowly, the dark water is sliced by thin light-brown patches. At first they are sparsely scattered here and there, but slowly they grow in numbers, like a small army gathering its troops. Soon, on both sides, we are escorted by trails of seaweed that, like us, follow the wind’s direction for miles on end.»

A few months earlier, the 11th of March, in Bermuda. The room is busy with men in three-piece suits firmly shaking hands in congratulations. It is a historical moment for the Sargasso Sea. The American, British, Bermuda, Monaco and Azores representatives just signed the «Hamilton Declaration». Notwithstanding the fact that this political agreement has no real legal constraint, it is unprecedented for an area in the high seas. «The Hamilton Declaration represents a rare oasis of joint voluntary action to protect this high seas gem,» says Kristina Gjerde, IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature) Senior High Seas Policy Advisor.

A few months earlier, the 11th of March, in Bermuda. The room is busy with men in three-piece suits firmly shaking hands in congratulations. It is a historical moment for the Sargasso Sea. The American, British, Bermuda, Monaco and Azores representatives just signed the «Hamilton Declaration». Notwithstanding the fact that this political agreement has no real legal constraint, it is unprecedented for an area in the high seas. «The Hamilton Declaration represents a rare oasis of joint voluntary action to protect this high seas gem,» says Kristina Gjerde, IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature) Senior High Seas Policy Advisor.

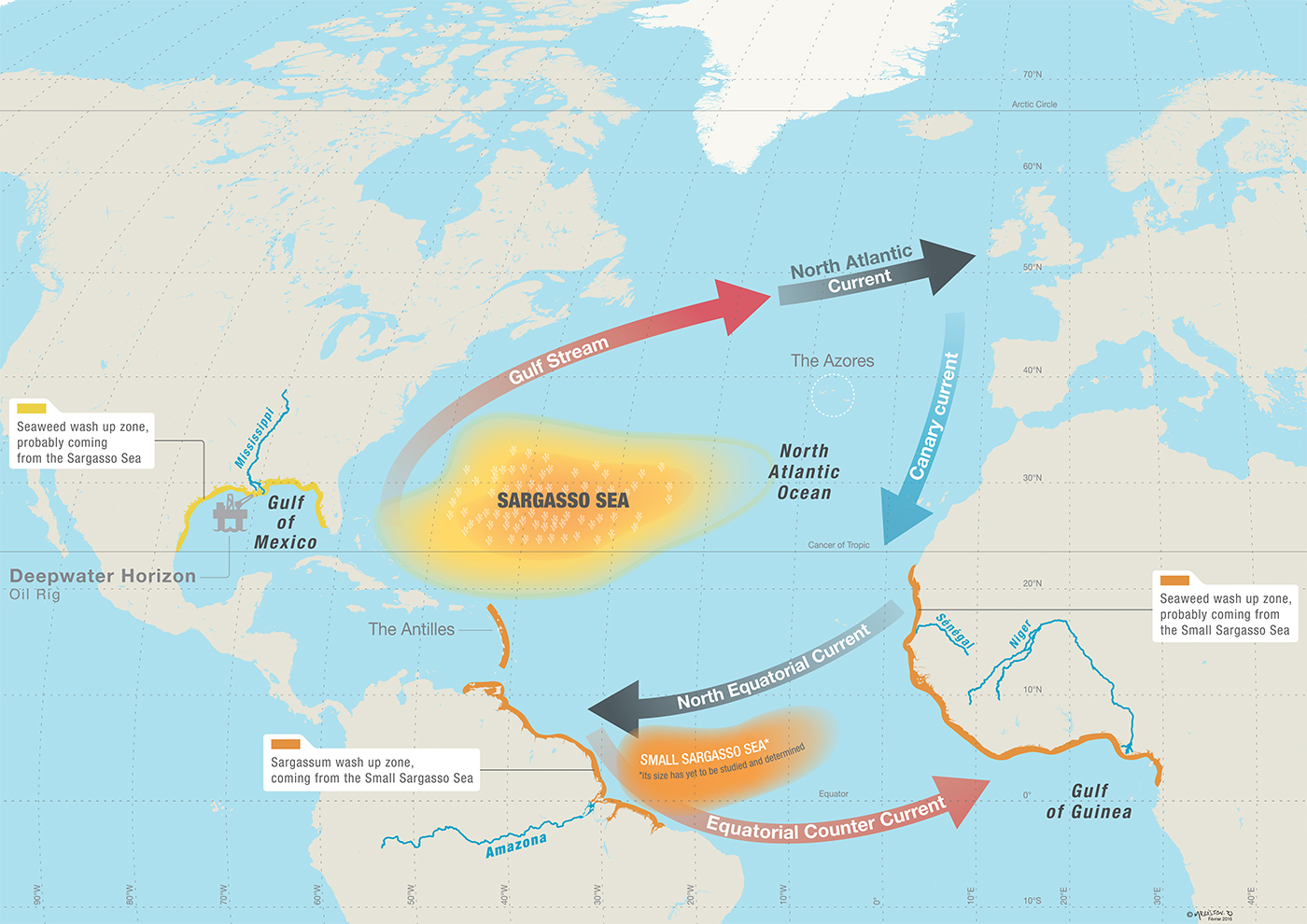

The Sargasso Sea is at the heart of a gyre, itself created by massive clockwise ocean currents. These enormous whirlpools can reach over tens of thousands of square kilometers. The one that we are interested in is situated in the North Atlantic, and is delimited by the Gulf Stream in the North-West, the North Atlantic current in the West, the Canary current in the South and the North Equatorial Current to the East.

More or less in the middle of these massive underwater torrents, a relatively calm water zone can be found, where sargassum have been growing and building up for centuries, maybe millennia. It is a very hostile zone, stretching far away from any coastline. In some places, it is 7’000 meters deep, and its water is very poor in nutrient. In other words, it is an oceanic desert. Around the globe, every gyre has its own. Nevertheless, in the North Atlantic, an aquatic forest managed to settle. There are no similar ecosystems anywhere else on our blue planet. To this day, its origins remain obscure.

Philippe Potin and Valérie Stiger-Pouvreau, two macro-algae specialists at the CNRS, both agree on the fact that the Sargasso Sea is a «unique ecosystem». Around the world, several hundred species of sargassum exist, and most of them grow on rocky substrate, close to the shore. In the Sargasso Sea, the two colonizing species are the Sargassum Fluitans and the Sargassum Natans.

December 17th, 2014 – Leenan Head’s logbook:

December 17th, 2014 – Leenan Head’s logbook:

«As our boat slowly and effortlessly slices forward, we put two fishing lines in the water for trolling. One of them holds back, but it’s not a fish that took the bait. When we pull it back on board, all we get is a big handful of sargassum. It’s weird, because we should now be navigating well South of the Sargasso Sea. The seaweed is about 40 centimeters long, brown to yellow in color, slimy and firm to the touch. Much like little shrubs with small leafy branches, they sometimes bear small fruits. As I find out, they are in fact little air bladders called pneumatocyst. While admiring these curiosities, the second line left trolling makes a catch. The crew starts running around as a one-meter long mahi-mahi splashes around in an attempt to free itself from the trap. Once on the deck of the boat, the beautiful blue green and yellow fish will lose its shiny dress in a few minutes.»

One year later, I am sitting in the UBO (University of Western Brittany) office, in Brest. I am speaking with the biologist Valérie Stiger-Pouvreau, and she explains: «One of these seaweed’s particularities is to float on the surface of the water. They have successfully colonized the North Atlantic gyre, but they still have to compete with the phytoplankton. Indeed, they both need sunlight to photosynthesize and grow.» But how can they grow in such a nutrient-poor environment? At the Roscoff marine station, Philippe Potin answers: «The sargassum seaweed is capable of absorbing the slightest traces of nitrogen. It is possible that some bacteria are part of the process. Studies are currently being conducted.»

It is estimated that more than 10 million tons of sargassum cover the area. They reproduce right here, in the middle of the open ocean. «The gyre’s sargassum don’t use a sexual reproduction system. They spread through cuttings, and their growth is quite slow, adds Valérie Stiger-Pouvreau. They are more or less clones, sharing the same genetic pool.» The biologists are actually trying to figure out if each member of its own species is a «clone» or if they are several specimens.

At the end of the day, our understanding of these algae’s physiology is rather small. Nonetheless, the scientific community agrees that they constitute an exceptional natural heritage and should therefore be protected. As early as 1996, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) realized the importance of the Sargasso Sea, and declared it «Essential Fish Habitat». When they accumulate in lumps or rafts, the seaweed offers outstanding protection for numerous life forms. Countless species use the algae carpet to reproduce and feed. Experts have calculated that a hundred types of fish have a direct relationship with the sargassum. Philippe Potin gives us precisions: «The sargassum release exudates of sugar and alcohol. They enter the food chain through the bacteria’s growth. The biofilm allows the fixing of microbial life, which is at the base of the whole food chain: fish, crustacean, turtles, marine mammals and birds all benefit from it.»

At the end of the day, our understanding of these algae’s physiology is rather small. Nonetheless, the scientific community agrees that they constitute an exceptional natural heritage and should therefore be protected. As early as 1996, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) realized the importance of the Sargasso Sea, and declared it «Essential Fish Habitat». When they accumulate in lumps or rafts, the seaweed offers outstanding protection for numerous life forms. Countless species use the algae carpet to reproduce and feed. Experts have calculated that a hundred types of fish have a direct relationship with the sargassum. Philippe Potin gives us precisions: «The sargassum release exudates of sugar and alcohol. They enter the food chain through the bacteria’s growth. The biofilm allows the fixing of microbial life, which is at the base of the whole food chain: fish, crustacean, turtles, marine mammals and birds all benefit from it.»

Among the key species we can find in the Sargasso Sea, the most famous is probably the Anguilla Anguilla eel, which is able to swim more than 6’000 kilometers from the European rivers in order to reproduce. We still don’t know why or how this prodigious migration takes place.

December 18th, 2014 – Leenan Head’s logbook:

«A few more days of sailing before we can reach the postcard perfect islands of the Caribbean. I am surprised to have seen so little macro-waste during the transatlantic crossing. They are hard to see, but it doesn’t mean that there aren’t there.»

If the currentology context allows the accumulation of seaweed in the gyre of the Sargasso Sea, it also allows the concentration of pollutants and plastic. Much like the four other biggest gyres scattered in the different seas and oceans of our planet, the one in the North Atlantic is a perfect opportunity for waste to coagulate, forming what we sometimes refer to as «garbage patches». In truth, these zones are hardly noticeable and are far away from the image we have of a 7th continent made of plastic. Under the unforgiving pressure of the waves, the waste is actually fractioned in microscopic particles, making them all the deadlier for the environment. Once reduced to a small size, these artificial particles can be ingested by the plankton, which in turns feed the whole food chain, all the way up to the apex predators.

«In the 2’000s, this important concentration of plastic became the perfect excuse for several American corporation who wished to collect 10% of the seaweed in the Sargasso Sea», Philippe Poton remembers, still shocked by such a bold proposition. «The biofuel market was booming, and they promised to scoop up all the plastic at the same time as the seaweed!» In reaction to this threat, several countries associated in order to protect this area rich in biodiversity.

But this threat was only the tip of the iceberg. A group of Canadian scientists identified the Gulf of Mexico’s North-West area as the sargassum’s spawning zone in spring. According to Jim Gower and Stephanie King, the young seaweed then reaches the Sargasso Sea around July, to join the existing biomass. Each year, one million tons would therefore be added, drifting along the current from the Gulf of Mexico to the Atlantic Ocean.

The problem is that the Gulf is often heavily polluted by dangerous chemicals. More than 4’000 oil rigs have been erected over the past decades in the North American waters. In 2010, the now notorious «Deepwater Horizon» rig exploded, with the dreadful consequences we all witnessed for weeks on live television. The authorities along with the company that owned the rig, BP, reacted to the massive oil spill by pouring seven million liters of Corexit in the Gulf, a powerful dispersant that dilutes the oil. The very same year, the Mississippi River saw the biggest flooding in the history of mankind. All the deadly terrestrial contaminants were washed into the already dirty waters of the Gulf of Mexico.

The problem is that the Gulf is often heavily polluted by dangerous chemicals. More than 4’000 oil rigs have been erected over the past decades in the North American waters. In 2010, the now notorious «Deepwater Horizon» rig exploded, with the dreadful consequences we all witnessed for weeks on live television. The authorities along with the company that owned the rig, BP, reacted to the massive oil spill by pouring seven million liters of Corexit in the Gulf, a powerful dispersant that dilutes the oil. The very same year, the Mississippi River saw the biggest flooding in the history of mankind. All the deadly terrestrial contaminants were washed into the already dirty waters of the Gulf of Mexico.

The Americans have a long-lasting relationship with the sargassum seaweed. Since the 1960s, from Texas to Florida, the coast has regularly been covered in S. Natans and S. Fluitans. The amount of washed seaweed only grew through the 1980s and 1990s. Sometimes referred to as the «Golden Tides», the arrival of these tremendous amounts of algae have always been associated with the Mississippi River’s runoff. The largest drainage system in North America carries all the washed away chemical fertilizers used on the farms along its shores.

Sometimes, these Golden Tides are beneficial to the ecosystem. All this washed up seaweed helps to slow coastal erosion, and allows numerous organism to colonies the beaches. The Americans have also worked hard to promote the sargassum, so that the unnatural phenomenon would be perceived as positive.

However, since 2011, other North Atlantic shores have started to suffer: some African and Caribbean coast are falling victim to these slimy golden tides.