Conversation with a homerist

Archaeologists and historians are not the only ones interested in discovering Odysseus’ legacy. The tales of the legendary king are told in two major texts: First in the Iliad, which describes the last days of a ten-year-old siege on the city of Troy. And in the sequel, the famous Odyssey, the reader follows the hero on his epic quest to come back home, sailing from one Mediterranean island to the other. Another decade of fantastic adventures to reunite with his family and his kingdom.

These two books have reached almost every human being, becoming a cornerstone in our modern literature and culture. No need to be an expert in ancient Greek to know that Odysseus and his sailors had to fend off dangerous mermaids, battle against cyclops and resist wicked witches. These legends easily made it to the core of our collective imagination, some say as much as the Old and New Testaments.

For many years, the two ancient Greek texts have been studied by experts called Homeric Scholars, or Homerists. David Bouvier is one of them, and is currently a Greek literature professor at the Lausanne University. His thesis was focused on Hector, prince of Troy and son of King Priam. He knows the Odyssey very well, and even went sailing the Ionian Sea on the hero’s tracks. We met with him on the shore of the Leman Lake in Switzerland, so that he could enlighten us on the many mysteries that still surround the texts and their author.

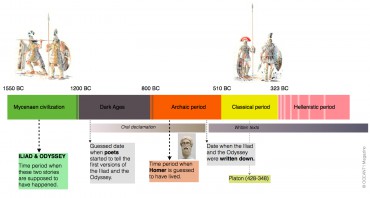

«To fully comprehend the nature of the Iliad and the Odyssey, we need to listen to the verses that compose them as lyrics that compose a song, David Bouvier explains. Before the words were actually written down for the first time around the 6th century BC, the tales had been sung and transmitted orally for many generations.»

«To fully comprehend the nature of the Iliad and the Odyssey, we need to listen to the verses that compose them as lyrics that compose a song, David Bouvier explains. Before the words were actually written down for the first time around the 6th century BC, the tales had been sung and transmitted orally for many generations.»

This is the first major problem we are confronted with when studying the texts: 500 years went by between the oral construction of the story at the end of the Mycenaean civilization, and the moment it was written down on paper in ancient Greek, never to be changed again. 500 years during which the taking of Troy and the return of the sailing king were exclusively sung by the bards of the dark ages, the aoidos. What can be confusing is that the elements of the classical Greek culture started to appear at the same time: the alphabet with Phoenician origins, the beginning of literature, the spawning of city-states with their specific politic functioning systems. It was a transitional period where things got mixed up.

The second problem, and most significant one, is that nobody knows for sure if the world described in the Iliad and Odyssey truly existed. Are the texts mere paintings of the forgotten Mycenaean civilization, with its palaces, kings and heroes? Or are they a precise portrait of the Homeric society in Greece, between the 10th and 7th century BC?

David Bouvier thinks these questions are impossible to answer: «The aoidos used past stories and legends to illustrate their present. They sang lyrics that weren’t historical nor fictional. The tales were definitely inspired by events in the past, but slowly altered to make them interesting for their local audience. The singers were prosody experts, giving importance to tonality, intonation, accents and modulation of the lyrics. With centuries of practice, their art evolved into a poetic language composed of verses that still today puzzles the top linguists. This unique language enabled the aoidos to recite what can be compared to oral encyclopedias. They had to adapt to their audience, in order to avoid embarrassing the prince or on the contrary to criticize him if he wasn’t around.»

This particular language is called hexameter verse. The reciting of a poem is rhythmed by incantatory formulas that are difficult to read but make sense when they are sang. Groups of epithets such as “Odysseus man of many resources”, “Great Hector of the shining helmet” or even “rosy-fingered Dawn” are plentiful in the texts, and they allow the aoido to structure the poem and breath for a second. These easy to remember formulas give enough time to think about the next verses and organize the rest of the text.

This process was first identified by the linguist Milman Parry, who conducted several studies in the 1930s in Serbia and Montenegro. At that time, it was believed that Serbian poets and traditional singers were very close to the ancient Greek aoidos of the Homeric era. Parry recorded long chants that were sung by “guslari”, these often analphabetic bards capable of reciting poems thousands of verses long. The linguist even noted that some guslari lost their incredible memorization capabilities once they learnt to read and write. One of the most sang tales is about the battle of Kosovo that took place during the 14th century, when the Ottoman army of sultan Mourad 1st fought the Albano Serbian Christian troops. Milman Parry noted that along the years, important facts had been changed in the lyrics by the guslari. More than a permanent text, the tales recited by the different bards are a matrix of verses in perpetual evolution.

Milman Parry thinks that with the years and the generations of story tellers, the original script of the taking of Troy and return of Odysseus must have changed quite a lot. Although one particular aoido made a name for himself in this particular genre, to the point where he was credited the paternity of the two legendary texts. His name was Homer.

He might have lived towards the end of the 8th century BC and is considered the father of the Iliad and Odyssey we still read today. According to the Greek historian Herodotus, he was originally from the island of Chios. He could have been blind, which helped the development of incredible memorizing and reciting skills.

Nonetheless, his mere existence is subject to conflict between the Homeric scholars. David Bouvier explains that «It is very difficult to have everybody agree on Homer’s existence. I personally like to think that the Iliad and the Odyssey are the fruit of an oral tradition that has been brilliantly captured and frozen once and for all.»

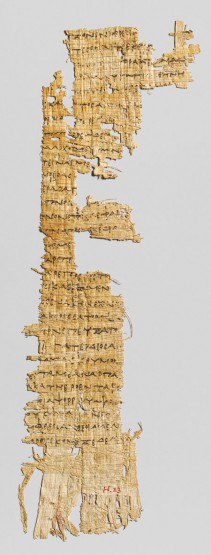

To add a layer of doubt to the delicate question of Homer’s identity, it’s important to know that his texts were transcribed for the very first time almost two centuries after his death. One of the privileged theories is that the mysterious transcription happened during the reign of Peisistratos, the tyrant of Athens in the 6th century BC. At that time, a religious festival took place during which rhapsodies were recited, mostly tales of heroes and their epic deeds. Homer’s poems could have been written down on parchments or papyrus in order to facilitate their memorizing, and structure the reciting to fit a certain norm.

In light of all this, it appears that the Odyssey should not be the most accurate tool to locate the legendary island of Ithaca. Many questions are still left unanswered: Was King Odysseus a historic character? Or an allegorical figure of a Mycenaean monarch who ruled over several small islands in the Ionian Sea? How much can we trust the geographic descriptions of Ithaca that we find in Homer’s poems?

«It’s hard to imagine Homer visiting the different spots in order to match his story with the reality, David Bouvier adds. It’s too modern a method». Nonetheless, even if Odysseus’ palace is still out of reach, many other places described in the texts have since been formally identified.

Even if Homer wasn’t able to visit all the places himself, it’s safe to assume that he had somebody describe them to him in great detail. Our Homeric scholar insists on a technical fact: the parts that structure the texts have different levels of importance. For example, in the first songs, Telemachus goes looking for his missing father. This introduction portrays the Greek society at a time when it was shifting from the Mycenaean civilization to the Homeric Greece. The same can be said about the last songs, when Odysseus finally reaches Ithaca and kills the pretenders who were too keen on stealing his wife and throne. This is where a rather precise description of Odysseus’ palace can be found, along with pieces of information on day to day lives of the protagonists.

Even if Homer wasn’t able to visit all the places himself, it’s safe to assume that he had somebody describe them to him in great detail. Our Homeric scholar insists on a technical fact: the parts that structure the texts have different levels of importance. For example, in the first songs, Telemachus goes looking for his missing father. This introduction portrays the Greek society at a time when it was shifting from the Mycenaean civilization to the Homeric Greece. The same can be said about the last songs, when Odysseus finally reaches Ithaca and kills the pretenders who were too keen on stealing his wife and throne. This is where a rather precise description of Odysseus’ palace can be found, along with pieces of information on day to day lives of the protagonists.

But things get complicated when we reach the passages on the fantastic journey from Troy to Ithaca, as Odysseus recalls them in front Alkinoos, the Phoenician king. David Bouvier explains: «Odysseus’ account is hard to analyze, it’s a story in the story and it doesn’t hold the same status as the rest of the text». As they were on their long journey home, Odysseus and his companions fell into a bizarre world filled with strange beings, mermaids, cyclops, witches and gods. How did the aiodos switch to this part of the tale, and make it orally understandable? At this stage of the poem, Odysseus is singing through the performer’s voice. This means the real audience is listening to a poet singing the story of a hero reciting his own story to his own audience, the Phaeacian king and his guests. A classic “mise-en-abyme” situation, very confusing if not done properly.

As the text goes on, the reader learns that Odysseus managed to convince the King Alkinoos. A boat is chartered by the Phaeacians to finally bring the hero back home. It’s a moment in the book where the reality seems to prevail over the fantastic. The timing is perfect for us to go back into the field, on the island of modern Ithaca, and keep looking for clues to resolve this 2000-year-old mystery.