Stolen paradise

Bernadette Dugasse wakes up startled. She doesn’t recognise the ceiling, and for a fraction of a second she doesn’t know where she is. Her ears pick up a foreign bird song, and suddenly the memories come flooding back as if she had just turned on the tap of an under pressure container. The bird sings again, and is soon followed by responses from further away. At this moment, Bernadette isn’t quite sure to have ever heard a more beautiful sound in her entire life. The smile on her face does nothing to hide the overwhelming feeling.

The night was short, and she doesn’t have the body of a 20 year old anymore. But the excitement is too much to bear. She forces herself out of bed. What lies behind that white door has been waiting for her since she was a little girl. After the sounds, it’s the fragrance of the place that she notices. She can’t explain it, but a memory is triggered deep inside her brain. Nothing is more memorable than a smell, and every place has its own. This one speaks directly to Bernadette’s forgotten childhood.

She grabs the knob, and for a split second she hesitates. When you are about to finally reach what you have been dreaming of for so many years, the feelings start mixing up. She can’t help but think of all the people she would like to share this moment with. The pain, the sadness, the anticipation, the happiness, they all come at the same time. The moment passes, and without noticing it she is standing outside, in the daylight. The scenery before her eyes surpasses her wildest dreams. She truly is in paradise.

Nothing is missing: the warm morning sun, the gentle sea breeze, the blue sky, the coconut trees and lush vegetation where tropical birds discuss the day to come. Bernadette doesn’t want to pinch herself in case she might wake up in her bed back home. The grey London suburb where she has been living for years seems a world away.

On her right and left are closed doors to other rooms. She is the first of a group of very special tourists to have woken up. She needs to speak to somebody right away and starts banging on all the doors. « Wake up! It’s daytime, come on! Get up! »

Her son is the first to come out, with groggy but happy eyes, and the rest of the group soon follows. They are 12 in total, and they all start speaking cheerfully at the same time in their own type of Créole, a French-derived language that is typical to postcard perfect islands. Less than 2’000 people in the world still know this particular “Créole Ilois.”

Part of the discussion is about the scenery, the singing of the birds and the smells. The other part is about the events that unfolded the night before.

Less than 24 hours earlier, Bernadette, her son and the rest of their group were in a waiting lounge at Singapore airport. After several hours, they were told that their plane was finally ready for boarding. Even though they knew it beforehand, it still came as a shock to walk up the stairs of a U.S. Air Force plane, the type of which passengers sit in front of each other at the back. Bernadette’s group shared the trip with Americans, British, Filipinos and Jamaicans.

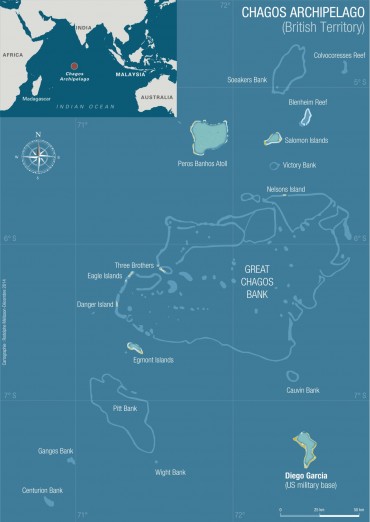

This heteroclite crew headed to an isolated location, where one does not simply book a plane ticket to : The island of Diego Garcia, the largest of the Chagos Archipelago.

To Bernadette and her friend’s great despair, the plane was scheduled to land at night time. They would not have the opportunity to see the island from above, and she can’t help but think that it was intentional.

At last the wheels touched the ground, and they were allowed to unbuckle as the plane came to a standstill. Outside, it was pitch black. « It was so dark, Bernadette told me during an interview. There were no lights in the airport. It is the first time I have landed at an airport that was so dark. We were really confused. »

The group of 12 is finally taken care of, and are given a meal and a room for the night. Their first experience of the nine day trip isn’t what they expected. Nonetheless their spirits are higher than they have been in years, and jokes and laughing soon resume.

They weren’t on Diego Garcia to take pictures of the immaculate beaches, to bath in the sea and the sun or to drink cocktails. They came to see where their parents and sometimes parents’ parents were born. Or like Bernadette, to set for the first time an adult foot on the island that saw her come into this world.

Diego Garcia isn’t on any tourist map. The Chagos archipelago doesn’t have its own Lonely Planet guide. One of the reasons is that it is so secluded, but mainly it is because its access is strictly controlled by two of the most powerful countries in the world.

Situated right in the middle of the Indian Ocean, the archipelago’s closest neighbours to the North are the Maldives, 750 kilometres away. Looking straight to the West at about 1’850 kilometres are the Seychelles. But water is everywhere around for hundreds of kilometres, as far as they eye can see. Blue, deep and virtually untouched.

Since 1965, the isolated archipelago has had a second name: The British Indian Ocean Territory, or BIOT. From the moment they were detached from Mauritius, the 55 tiny patches of land that hardly make it over the Indian Ocean have been manipulated by the Foreign Office in rainy London, 9’500 kilometres away.

Surprisingly enough, the British aren’t a majority in the BIOT. While visiting their native island, Bernadette and her friends saw an awful lot of people. And they weren’t tourists. They came and went in khaki vehicles, and were wearing camouflage uniforms with a clearly recognisable flag sewed on their shoulders: the banner of the United States of America.

These soldiers work on the U.S. military base of Diego Garcia, where aircraft carriers, nuclear submarines, B52 bombers as well as several thousand soldiers can be found depending on the international geo-political status. The island is also headquarters for the GEODSS space surveillance program. The U.S. currently runs some 1’000 military bases and installations on sovereign land of other nations. The size of the compound on Diego Garcia as well as its range of activities makes it the largest and most important of them all. One base to rule them all, as it has been called “the indispensable platform for policing the world.”

In 1971, when the construction started, they were no natives in the Chagos Archipelago. Or so that was what the Americans were told. Indeed, the single most important condition for the construction of the highly strategic base was the absence of adjacent civilian population, for “security reasons”. The truth is people had been living in the archipelago since the 18th century.

Navigators knew about the islands for centuries, being at such a central place for stopovers in the Indian Ocean. But Diego Garcia had to wait until 1793 to see a successful permanent settlement. First by French and then by British colonisers, who started a coconut plantation with the help of dozens of slaves. In 1834, slavery was outlawed and the freed workers became employees. Many decided to stay on the islands and work for the European managers on the coconut plantations. In the archipelago, life wasn’t easy by any means. However, the Chagossians’ culture flourished and the local people were happy, living on farming the tropical land and fishing the lagoon’s waters.

However, in the 70’s, the British tricked the approximately 1’500 Chagossians, who were forced to abandon their home. It happened in stages over several years, but one by one they finally resigned to pack what they were able to carry and climb on boats that shipped them mainly to Mauritius and the Seychelles.

Bernadette was two years old when her family had to board, in the middle of the night, the vessel that would change their lives. « I was too young to remember, so my story is based on what my mother and my adopted grand-mother told me. We were expelled in 1972, with the last group of natives. »

To satisfy the requirements of the Americans who wanted an island “swept and sanitised”, the mostly illiterate Chagossians were dumped in the slums of their new islands, sentenced to never come back to their native country.

Some of the kids were able to go to school while their parents did whatever jobs they could find. Deep in poverty, many died of drug and alcohol abuse, of deceases and of sadness. Some committed suicide. Years passed, and the Chagossians’ ordeal slowly made its way to the public’s ears. The descendants started to regroup and organise into small communities. But the road to justice is often long and treacherous.

Several times, the case was brought to court in the U.K. and the Chagossians’ lawyers were successful in proving that the eviction was illegal. Compensation was paid, but the British and U.S. government never allowed a right to return. A master game of confusion was set in motion, and is still being played. The U.S. and U.K. smartly blame the refusal on the other, sparing neither effort nor ingenuity.

Such has been the lives of the people of Chagos. Their battle against two of the most powerful countries on earth has brought nothing but moments of hope that were later shattered to pieces.

A serious blow to their expectations came in 2010 when the largest marine park in the world was created, capturing the Chagos Archipelago into a banned fishing area. An international partnership of the PEW Charitable Trust, the Bertarelli Foundation, the Chagos Conservation Trust and the BIOT was able to establish a no-take marine reserve the size of France. With Diego Garcia right in the middle.

According to the IUCN, there are six categories for protected areas. The Chagos Marine Park is in the strictest category, where absolutely no extracted use is permitted. Less than 1% of the world’s oceans are protected as strictly as the Chagos Archipelago. This means that in the middle of the Indian Ocean, a huge area acts as safety zone for 800 species of fish, 220 different types of coral, many plants and birds and turtles. But it also means the Chagossians, if ever permitted to resettle, will not be allowed to fish for subsistence.

The native population has been systematically set aside during the creation of the Chagos MPA, unlike what is considered best practice around the globe for the establishment of natural reserves. Ironically, at the Chagos Conservation Trust conference in London at the end of 2013, it was said that the MPA was understaffed and badly needed additional workforce.

Richard Dunne, who participated in the Chagossians’ legal battles for the right to return, told me that according to his experience, « not more than 150 people would be willing to resettle. » They have been uprooted for decades, and are of course not willing to go back to a life of semi slavery in a coconut plantation. On the contrary, they are looking for meaningful jobs, such as the one the MPA could offer. They would also be willing to work for the U.S. military base. But this is something that has been denied to them, time and again. Instead, mainly Filipinos have been hired as an exterior workforce on the base.

Olivier Bancoult, the leader of the Chagos Refugee Group, is actively working for a resettlement on the northern islands. Located more than 200 kilometres away from the U.S. military base, they are the only two places where private yachts are allowed to anchor for a limited period of time – the only tourist activity of the archipelago. But Bernadette will never agree to resettle on Peros Banhos atoll or on the Salomon atoll : « When I was on Diego Garcia in 2011, I felt a deep connection to the place. Even though the northern islands are beautiful, I won’t go and live there, because I didn’t feel any connection. And I fear that if we accept to resettle in the north, the island of Diego Garcia will forever be off the table. I will never accept anything less than the full resettlement on the island of our choice, the place where our ancestors were born and buried, » she firmly says.

According to an extensive report published by KPMG in November 2014, the return of an oppressed group of people will not negatively impact one of the most pristine and protected marine places in the world. But history hasn’t been kind to minorities that seek justice against superpowers. Bernadette and her generation have truly lost their paradise, and the struggle of David against Goliath will most likely outlast them all, drowned in the maze of international bureaucracy.